In a New Mexico park, the buried bodies of Native American children are evidence of genocide

In a quiet tree-lined park a few blocks from downtown Albuquerque, small orange flags flutter in the wind, marking the graves of dozens of Native American children.

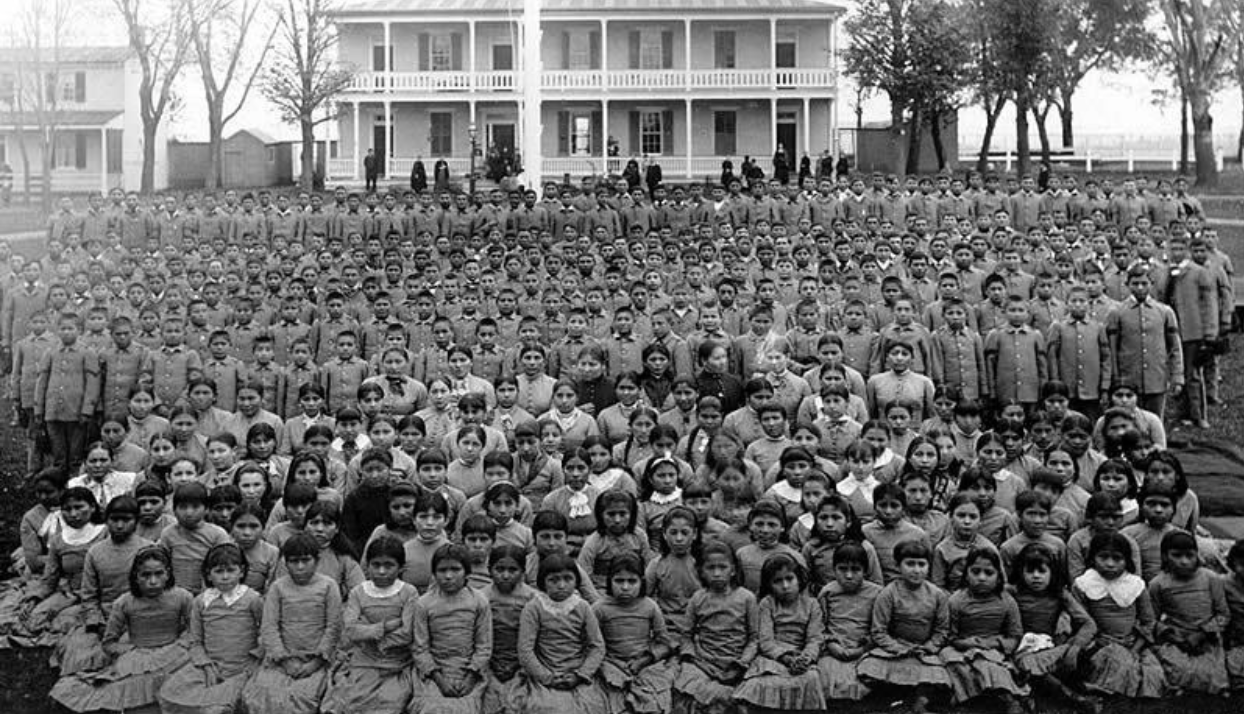

The graves belong to children who died at the former Albuquerque Indian School, where an estimated 1,000 Native American children from across the West were brought from 1881-1981. Authorities believe most of the graves belong to children killed by illness.

Launched by the federal government under the Indian Civilization Act, the network of an estimated 350 Indian Schools forcibly indoctrinated Native American children with the cultural and religious values of white Anglo-Saxon society, and taught them Western trades like farming, building or housekeeping. At their height, the schools were home to 60,000 children annually.

“It wasn’t education for enlightenment and empowerment. The goal was to Westernize them so there wouldn’t be a an Indian problem anymore,” said Ted Jojola, a member of the Pueblo of Isleta, whose parents attended the AIS. “They were on a mission, literally, on a mission from God.”

We all have a unique perspective: Sign up for This is America, a weekly take on the news from reporters from a range of backgrounds and experiences

Now, city leaders in Albuquerque have formally apologized for their predecessors’ role in creating and maintaining the AIS, becoming possibly the first U.S. government entity to offer such an apology. And many Native Americans hope that apology prompts the U.S. federal government to take a similar step in acknowledging what they call a genocide against their people. Albuquerque officials are still considering what next steps to take.

Most of the schools were run by religious groups at the behest of the federal government, which wanted to “civilize” indigenous Americans, weaken their power and take their land as the United States aggressively expanded to the west.

Although reliable records have been destroyed, authorities and tribal leaders say the children buried in what is now Albuquerque’s 4-H Park primarily died from diseases like malaria or the Spanish flu, or other communicable diseases for which they had no immunity.

‘Strangers in their own communities’

Experts say wrenching tens of thousands of Native American children from their families and immersing them in Western culture undermined tribal bonds, weakened families and caused generational trauma that’s still felt today – from poverty to obesity and heart disease.

The Canadian government has already apologized for its role in creating and supporting the church-backed schools.

Like tens of thousands of young indigenous Americans, Jojola’s parents were removed from their community – founded in 1300 about 25 miles away from what is now Albuquerque – by white Indian agents and school superintendents. Jojola’s parents graduated from the AIS in 1937, and he grew up hearing the stories of how they were humiliated or punished for speaking their tribal language, Tigua, in the presence of white teachers.

Jojola, 69, said his parents were lucky: While AIS administrators treated most students well, kids who attended other schools were beaten regularly. Other children vanished forever. Sometimes their parents were told of their deaths. Rarely were the bodies returned home, and instead were buried in Christian cemeteries.

Even the survivors who graduated and returned to their tribal homes were utterly different, dressed in Western clothes, speaking a new language, worshipping a Christian god, indoctrinated in capitalism.

“When they came back, they were essentially strangers in their own communities,” Jojola said.

The first Indian Boarding School opened in 1879 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and officials since 2016 have been working to repatriate the bodies of Native American children buried there.

In Albuquerque, officials don’t have a specific plan to address the burials in the park. Instead, they’re asking Native American leaders of the sovereign tribal nations to guide an ongoing process, which will likely include using ground-penetrating radar to map the bodies. Some families may want their children returned. Others may want to leave the dead buried, said Mayor Tim Keller.

Authorities say it’s possible children from the Navajo, Apache, Ute, Hopi and Pima tribes were forced to attend the school during its approximately 100-year existence. Keller said the apology is a starting point toward healing.

“We were clear that it was an acknowledgement and a reflection but that it was also just a beginning,” Keller said. “You’ve got to start by acknowledging the pain you’ve caused.”

‘We did not do this to ourselves’

The city acquired 4-H Park in the early 1970s, knowing that it has been used as a burial site for at least 50 years. Fires and floods at the school had destroyed what few records were kept, city officials said, and workers installing a sprinkler system unearthed a child’s body in 1973.

City officials installed a small plaque marking the burial site, but otherwise opened the park to public use. At some point in 2019, someone stole the plaque, setting off a new round of introspection, Keller said.

“The descendants of the people buried in that park literally still live here,” Keller said.

‘Missing White Woman Syndrome’: The Gabby Petito case has left Indigenous people asking how to ‘qualify’ for same attention

Like many Native American leaders, Christine Diindiisi McCleave, CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, welcomed Albuquerque’s apology. But she also remains skeptical because the bodies were largely ignored for decades.

Diindiisi McCleave, 46, is a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota. She said the longtime reluctance of Albuquerque and the U.S. as a whole to acknowledge the impacts of the boarding schools remains an open wound. Studies have shown that children subjected to intense trauma suffer lifelong impacts, including poor health, Diindiisi McCleave said, and those impacts persist in their descendants.

“There’s this narrative of American exceptionalism, and how America is great. And there are many great things about this country,” she said. “But until we recognize that this started in genocide, we are never going to be a truly great society. We did not do this to ourselves. We were existing happily and healthy until a bunch of people came to invade our lands. And that’s the narrative that the United States has kept silent.”

Diindiisi McCleave said she hopes the Biden Administration will help advance the coalition’s cause of acknowledging and healing the pain caused by the Indian Schools.

Last year, then-Congresswoman Deb Haaland, representing New Mexico, introduced legislation to create a Truth and Healing Commission to study the Indian Schools. Although the bill didn’t advance, Haaland did – she’s now the first Native American cabinet secretary, running the Department of the Interior in the Biden Administration.

In June, Haaland formally launched a federal study on boarding schools, including their locations, attendance and any associated burials. The study’s first report is due April 1, 2022.

‘The tip of the iceberg’: Mass grave of 215 children in Canada a stark reminder of the dark history of Native American boarding schools in US

“Only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future we are all proud to embrace,” Haaland wrote in launching the investigation. “Many who survived the ordeal returned home changed in unimaginable ways, and their experiences still resonate across the generations.”

The Canadian government in September marked its first National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, a remembrance that followed the discovery of hundreds of children’s bodies buried on the site of a former Indian School in British Columbia. The Canadian government has also paid tens of millions of dollars in reparations to the families of children who attended the schools.

Jojola, a professor at the University of New Mexico who directs the university’s Indigenous Design and Planning Institute, said the metaphor of the children’s callous and largely unmarked burials is hard to escape.

“The people who ran the boarding schools, they literally wanted to bury the egregious acts they committed,” he said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Native American children’s graves in city park show appalling history