WARNING: This story contains disturbing details about residential and boarding schools. If you are feeling triggered, here is a resource list for trauma responses from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in the U.S. In Canada, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Hotline can be reached at 1-866-925-4419.

This story and a two-part podcast are the result of a collaboration between ICT and Reveal to examine Indigenous boarding schools in the United States. The podcast, “Buried Secrets: America’s Indian Boarding Schools,” starts with part 1 that aired Oct. 15 and concludes with part 2 that aired Oct. 22.

Mary Annette Pember

ICT

PINE RIDGE INDIAN RESERVATION, South Dakota – Justin Pourier will never forget what he saw in the basement of Drexel Hall.

Pourier, a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Tribe, was working as a bus driver and maintenance person for the Jesuit-run Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge reservation when sometime in the 1990s a supervisor asked him to go into the basement to look for a leak.

Pourier made his way down the rickety steps to the vast basement below Drexel Hall, former home to student dormitories and later a convent for nuns who taught at the school.

SUPPORT INDIGENOUS JOURNALISM. CONTRIBUTE TODAY.

Back in a corner, past a wooden door that led into a small room with a dirt floor, he saw three small mounds of dirt. Evenly spaced, shaped like child-size graves, the mounds were marked with primitive crosses.

“Right away, I knew that wasn’t right,” Pourier told ICT and Reveal in May.

LISTEN: Part 1https://open.spotify.com/embed/episode/6aOSEFd1xw1HQRdJuUIdXu?utm_source=generator

LISTEN: Part 2https://open.spotify.com/embed/episode/55ZvPgZnXeZSvmUFLUVJ5i?utm_source=generator

After learning of the discoveries of unmarked graves of children who attended residential schools in Canada, Pourier reached out to Red Cloud leaders earlier this year and told them his story.When he told his supervisor about his discovery, however, the man grew angry, demanding that he never discuss his findings with anyone.

And so, Pourier obeyed. Until now.

After learning of the discoveries of unmarked graves of children who attended residential schools in Canada, Pourier reached out to Red Cloud leaders earlier this year and told them his story.

By then, Red Cloud had already launched a Truth and Healing effort amid growing pressure to reveal the truths about the school’s boarding school past.

Red Cloud is a microcosm of the issues facing churches, government leaders and Indigenous people over the nation’s sordid boarding school history, and could provide a blueprint for other schools in years to come.Now a day school that provides education to about 600 Indigenous students from kindergarten through high school, Red Cloud is among the first of the former Indian boarding schools in the United States to actively work toward truth and reconciliation.

“It’s important we explore our history and own our past,” Red Cloud President Raymond Nadolny told ICT/Reveal. “This is a strong, fierce community. We’re excited to get these conversations on the table.”

Red Cloud is a microcosm of the issues facing churches, government leaders and Indigenous people over the nation’s sordid boarding school history, and could provide a blueprint for other schools in years to come.

The Truth and Healing efforts, so far, however, have uncovered more questions than answers.

A seven-month review of the Red Cloud school by ICT and Reveal found evidence of at least one unmarked grave and at least 20 student deaths, and harsh, dehumanizing treatment of students at a time when the Catholic Church was accumulating thousands of dollars in government payments and hundreds of acres of land at the expense of the Oglala Lakota people.

From 1903 to 1940, records show the church received the equivalent of nearly $18 million in today’s dollars via the U.S. government from Lakota trust and treaty funds for providing education to Indigenous students at Red Cloud, and obtained more than 700 acres of tribal lands for the mission and school, the ICT/Reveal review found.

Today, the nonprofit organization that now runs Red Cloud also operates another elementary school, six community churches and the Heritage Center art gallery. It reports $82 million in assets while based in a county, Oglala Lakota County, that ranks among the poorest 25 counties in the U.S.

And though Red Cloud officials have vowed to uncover the truths of their boarding school history, the Catholic Church’s openness with records has fallen short of expectations. The lack of transparency prevents researchers from determining how many children attended boarding schools across the United States and keeps family members from knowing what happened to their missing relatives, ICT/Reveal found.

“The Catholic Church needs to recognize that honesty, being forthright and vulnerable, are far more powerful and more healing than being reticent, restrictive and closed,” said Maka Black Elk, Oglala Lakota, who was hired in 2020 as executive director of Truth and Healing for Red Cloud.

ICT/Reveal also reached out for comment to Jesuit leadership internationally in Rome and in the U.S., the Vatican, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and the head of the Bureau of Catholic Indian MIssions. Officials did not make themselves available for interviews.

And while Red Cloud is being lauded by some for its efforts, others question whether an independent investigation might be more truthful.

“How can we let them investigate themselves?” asked Dusty Nelson, a citizen of the Oglala Lakota tribe and a former student at Red Cloud who has been an outspoken critic of Jesuit leadership.

Some questions may be answered in coming weeks. Red Cloud is set to begin excavation on Monday, Oct. 17, in the Drexel Hall basement where Pourier believes he saw the small graves.

Ground-penetrating radar of the site in May was inconclusive on what might lie beneath the ground, and officials agreed to dig up the concrete slab that now covers the area.

The ICT/Reveal findings will be featured in a two-part podcast, “Buried Secrets: America’s Indian Boarding Schools,” that starts with part 1 on Saturday, Oct. 15, and concludes with part 2 on Saturday, Oct. 22.

A long history in Lakota country

It was a hot July on the South Dakota prairie in 1888 when a Jesuit priest known as Father Jutz escorted four nuns from the Sisters of St. Francis of Penance and Christian Charity to Lakota country to teach Indigenous children at the newly built Holy Rosary Mission School.

Clad from head to toe in black habits and head coverings, the nuns arrived to greetings from Lakota leaders under the prairie’s unrelenting summer sun, with temperatures likely reaching into the 90s.

Seeing women for the first time with the Black Robes, as the Lakota people called the priests, the tribal leaders were curious.

“Are these your wives?” they asked Jutz, according to a written history by the Sisters of St. Francis that recounts the exchange. The diary was originally written in German but the archives include a version translated into English.

Jutz was apparently flummoxed into silence by the question, so one of the nuns responded.

“No,” she said. “[We’ve] come only for the sake of the Indians.”

Jutz had arrived in Lakota country to open Holy Rosary in 1887, two years before Congress created the Pine Ridge reservation in an effort to reduce the size of the Great Sioux Nation.

Catholic historians say that Lakota Chief Red Cloud invited church leaders to his country to educate Lakota children. Seeing the inevitable encroachment by the White man on his peoples’ lands and way of life, they say, Red Cloud saw the similarities between the church’s use of ritual and that of Lakota holy men.

Others disagree with the church’s perspective. Nelson, who said she is descended from Chief Red Cloud, believes the leader wanted to help his people navigate a major change in their society and lives. If he had known about the often-brutal assimilationist methods at the school and the goals of destroying Lakota culture and language, he never would have allowed them access to the children, she said.

Regardless of the long-ago motivations, the Catholic Church and its emissaries remain today on Pine Ridge, their existence intertwined with the fabric of the community for more than 130 years.

Much has changed at the school since the early days. The name was changed to Red Cloud Indian School in 1969, and the school stopped boarding students in 1980.

Its mission no longer includes destruction of Indigenous culture, spirituality and language, and now offers classes in Lakota language and culture. It employs tribal citizens as teachers and administrators.

And in keeping with the Jesuit reputation as rigorous educators, Red Cloud leads the nation in producing Gates Millennium Scholars per capita, with 72 students having received the honor as of 2016. An estimated 90 percent of graduates attend college.

That’s quite a feat in a community with a 70 percent high school dropout rate, and many Red Cloud graduates go on to attend Ivy League colleges and universities. Still, the school has rigorous admissions requirements and requires significant family support, which many students on Pine Ridge may lack.

“Since Red Cloud is a private school, they can set their own standards for entrance and attendance,” said Dayna Brave Eagle, director of the Oglala Sioux Tribe’s education department. “Tribal and public schools, however, don’t have that luxury.”

Nonetheless, there is a community of loyal Red Cloud supporters in Pine Ridge that includes generations of families who have graduated from the school and who take great pride in their ability to excel in the Jesuit’s demanding environment.

Related stories:

—Red Cloud school will dig for graves

—Catholic Church siphoned funds paid to Native people for stolen lands

—Deaths at Chemawa

—Sometimes we hear the voices of children playing there’

—’We carry the trauma in our hearts’

—’Our ancestors risked their lives and freedom’

—Churches starting to face facts on boarding schools

—’This place is the devil’

—Canada, US differ on boarding schools

—We won’t forget the children

—Death by civilization

—’We have to know it to heal it’

Jesuit leadership proudly points out that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito visited the school in 2011. And six of the current Supreme Court justices attended private Catholic schools, with Justices Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh attending Jesuit schools.

The school’s latest effort, the Truth and Healing review, likewise has the support of the Jesuits, Nadolny said. They have allocated $20,000 to the school for the work and recently supported bringing in the ground-penetrating radar to search for graves on campus. The Jesuits have allocated another $50,000 to pay one year’s salary for an archivist to examine their boarding school records in St. Louis.

The radar found no evidence of graves under the school lawn, but the results in the Drexel Hall basement were inconclusive.

Unlike the discovery of unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada, however, the potential for graves in the basement of Drexel Hall raise more sinister concerns. Tribal leaders and federal authorities will be on hand for the excavation.

“Red Cloud wasn’t a boarding school in the 1990s [when Pourier saw the graves] so we will be involving law enforcement, in addition to members of the community, when we excavate the area,” Black Elk said.

The revelation of Pourier’s findings has caused a stir in the community, with some calling for closure of the school while outside investigators search for evidence.

In August, Jesuit Father General Arturo Sosa visited Red Cloud school and offered an apology for the Jesuit’s role in assimilationist boarding school policies and actions, but many people in the community were not aware he was there until after he had left.

Harsh conditions

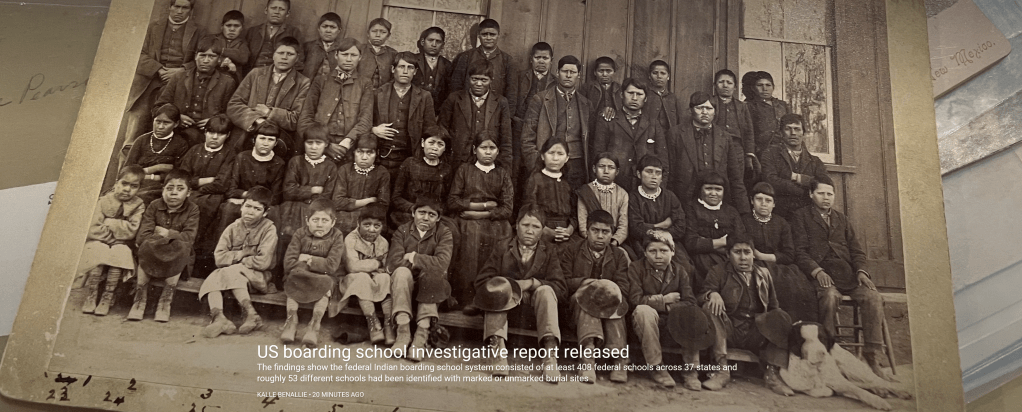

More than 1,000 graves have been discovered at Indian residential schools in Canada, where the searches continue, and more than 50 burial sites have been identified so far in the U.S. among the 500 Indian boarding schools that received federal funding.

The remains of more than two dozen children have already been returned to their tribes after being discovered on the grounds of the former government-run Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, and more than 170 are still buried there, records show.

The search is ongoing, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Rumors of missing students and unmarked graves have circulated around Indigenous boarding schools for years, including in the Pine Ridge community, and a number of other private schools across the U.S. and Canada are joining Red Cloud in searching their grounds for evidence of graves.

“These stories are rooted in horrific truths of the broader boarding school past,” said Black Elk.

The stories regarding Red Cloud school, however, have seldom included eyewitness testimony, at least until now, and the community is hoping for answers.

“This is a hard conversation for our community to have,” Black Elk said. “If our GPR work helps open the door to those conversations, then hopefully that leads people to healing.”

Nadolny did not dismiss the possibility of examining a larger area of the school grounds – an effort he estimated could cost millions of dollars.

“It’s something that might have to be done,” he said. “I think it’s important that the Truth and Healing work be Indigenously-led … As we have credible allegations of graves, we will address it.”

ICT and Reveal found evidence that at least 20 students died at the school – and another was sent home to die – in a review of documents at the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Archive at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; at the National Archives in Kansas City, Missouri; and at Red Cloud school.

Data, however, is scant, and the handwriting is sometimes difficult to read. The records often do not include any indication of how the children died, and their tribal affiliations are often redacted.

Among those was Zora or Zona Ironteeth, 7, who died in 1915 of unreported causes and was buried in the Catholic cemetery next to the school, according to the written history maintained by the Sisters of St. Francis. The written account covers a 40-year period at Holy Rosary Indian Mission, from 1888 to 1929.

ICT/Reveal found Ironteeth’s name and the location of her grave on a large, handwritten map of the cemetery at Red Cloud school, but was unable to locate a marker for her grave at the designated site during a search of the grounds.

The nuns’ written history mentions several other student deaths at the school as well. Some entries include the names and causes of death, and others simply state the number of student deaths during select years.

In 1888-1889, the first year the school year was open, seven student deaths were recorded out of the 130 students who attended. Only the first child who died at the school is identified — Ignace Black Face, who died at the mission in 1888 or 1889.

Other students identified in the nuns’ history as having died at the school over the years include Etta or Ella Shangreauw or Shangrau, 1895; Clara Condelario, who died in 1915 from tuberculosis and other health issues; Harley Cook, who died in 1925 at age 16; and Lawrence Clifford, who died May 1, 1926, of double pneumonia.

ICT/Reveal found death records from the National Archives for Etta/Ella and Harley, and an additional child, Rosa Red Elk, who died in 1907 at the mission but whose name was not found in the written history.

Tim Giago, of the Oglala Lakota Nation and founder of Indian Country Today, now ICT, also recalled digging a grave for his friend Bozo Richards, who died at age 16 during the years Giago attended the school, from the late 1930s to the early 1940s. Giago spoke to ICT/Reveal in May, just a few months before his death in July 2022.

Official death reports on the Pine Ridge reservation are sparse, relying on information filed with the federal Indian agent by farmers who lived in districts on the reservation. The White farmers were paid to report the information, but seldom included age, cause or place of death, according to a Bad Lands Resource Study from 2006 by the National Park Service.

In searching the region’s newspapers, ICT found no information regarding deaths or obituaries on the reservation from late 1800s into the 1920s.

Further complicating the search for student deaths, moreover, is that the cemeteries associated with Christian missions served not only the schools but also the entire community.

According to the nuns’ written history, seriously ill children or the remains of those who died were often retrieved by their parents, since most of the children attending Holy Rosary were Lakota from the Pine Ridge reservation. Unlike federal schools that were usually located far from tribal communities, parents were better able to travel to Christian mission schools, frequently located on or near reservations, to collect their ill or dead children.

Records indicate children at both federal and Christian schools often died from contagious diseases exacerbated by overcrowding, poor living conditions and inadequate food.

At Pine Ridge, the nuns’ written history describes waves of illnesses moving through the school, including measles, mumps, flu, trachoma, “skin disease,” tuberculosis, smallpox and typhoid.

In 1911, a Catholic doctor told the nuns that the children were sleeping too closely together, and the nuns converted the kindergarten into a sick room, the history recounts. Another entry blames children for bringing disease into the school after they were allowed to return home for a visit.

Tuberculosis, often referred to as consumption, was a persistent problem, among the nuns as well as the children.

A 1910 entry in the nuns’ history describes a government doctor finding that one of the nuns had “consumption” and ordering her to stay away from the children.

And in 1914, parents at the Holy Rosary Mission complained to the Indian agent that their children had gotten consumption from the sisters, according to the written history. A government doctor visited the school and issued orders for the school to collect information on deaths and illness.

The sisters did not take kindly to the criticism, with an entry in the history complaining of excessive government interest in “corporal benefit of the Indians.”

The same year, the Pine Ridge Indian agent responded sharply to a government circular urging quarantine for contagious diseases.

“The position of agency physician on this reservation has been vacant for five months. We have no reservation hospital or other place for suitable isolation. There is considerable suffering among the Indians here,” he wrote.

Other health problems spread throughout the school. A government doctor making a 1913 visit found nearly 100 children had trachoma, now known to be a bacterial infection that can cause blindness. Later, three government doctors came to the school and conducted “operations” on the children’s eyes in the parlor, the written history notes.

“Nothing else could get done because of care being given to the children,” the author complained.

Some terse entries suggest poignant stories of death, suffering and abuse.

An entry in 1915 describes the short life of Clara Condelario, who appeared to be in her early 20s when she died. She is described as an orphan who came to the mission in 1890 after the deaths of her Mexican father and Indigenous mother.

“She asked to remain at the mission (after her schooling was completed) and live like the sisters; they accepted her work around the house,” the entry notes.

“One day whilst scrubbing in the church she slipped, knocked her elbow on a bench and broke her arm. She didn’t tell the sisters until the arm pained her so much she could hardly dress herself. They sent her to hospital in Omaha where they put her arm in a cask [sp]. After we removed it things were not as they should be so we prevailed on her to return to hospital.”

The doctor who examined her found several sores on her body, and concluded she also had appendicitis. When they operated, however, they found her intestines were decayed from “tuberculosis of the stomach,” which can cause abdominal pain.

“There was nothing they could do, she died a few days later,” the entry concludes. “A requiem was held. She was the first Sioux girl to make a vow of chastity. She is buried near the sisters in the cemetery.”

Physical abuse, especially in the earlier years, was ever-present, former students told ICT/Reveal. Basil Braveheart of the Ogala Lakota tribe recalls the strict environment when he attended Holy Rosary School more than 80 years ago. Braveheart, now 89, said teachers used corporal punishment for even the smallest violation of school rules.

In addition to beatings, Braveheart described the emotional and spiritual abuse of being separated from family and being forbidden to speak the Lakota language.

“The experience was very traumatizing to me as a child,” Braveheart said. “Our language is what defines our culture. Having it taken away was a spiritual violation.”

Physical punishment is also mentioned in the historian’s entries. One describes a parent known as a “troublemaker” who complained to government inspectors about heavy-handed punishment meted out by the nuns and priests. The complaint drew a response from the inspector.

“The inspector suggests we use a strap rather than a stick to beat the children,” the history notes.

Other mentions of student deaths at Holy Rosary appear mostly in passing. An entry from 1913 mentions that an 8-year-old boy died from eating “a great quantity” of elm blossoms.

An entry in 1918 reads, “the flu comes, many die, funerals every day, authorities keep Indians away from the mission.” And in 1920, “children sick from smallpox, forbidden to return home.”

An entry from 1927 notes there was “much sickness” at the school and on the reservation, noting that three children died at Holy Rosary and more than 300 “babies” died on the reservation.

Additional details are believed to be included in the school’s sacramental records, but church officials have refused to open them up for scrutiny over privacy concerns. And whatever grave markers may have existed have long since crumbled.

Financial rewards

The Catholic Church benefited financially, however, for every child who attended the Pine Ridge school, receiving government, church and private funding.

Moreover, the church gained substantial political and economic influence in the U.S. through its work with Native peoples.

“The political weight of the Catholics in the nation and their successful lobbying for their interests in the Indian school question gave them a more widely accepted role in the national affairs, and it is no longer possible to think of management of Indian affairs without some consideration of Catholic views,” Jesuit scholar and priest Francis Paul Prucha wrote in 1979 in the book, “The Churches and the Indian Schools: 1888-1912.” He died in 2015.

For more than 65 years, until the 1970s, the U.S. government diverted Indian trust and treaty funds as direct payments for tuition to Christian boarding schools until funds grew depleted, according to the Marquette website. Catholics operated most of the schools and received the lion’s share of the funds, as well as other federal dollars.

Nadolny told ICT/Reveal that the possibility of paying reparations to the tribe is open for discussion.

“That’s a good conversation to have with the tribe,” he said. “Everything is on the table.”

Raymond Nadolny was tapped to be president of Red Cloud Indian School in 2019, the is the first non-Jesuit to lead the school. He is shown here in front of Drexel Hall on the Red Cloud campus. (Photo by Mary Annette Pember/ICT)

Records indicate that Holy Rosary school received $108 per student as early as 1903, which would have meant a yearly payment of $21,600 – the equivalent of more than $700,000 in today’s dollars – for the 200 students typically enrolled at the time.

By then, government payments to churches for educating Indigenous students were routine.

The federal government began paying Christian missionaries to “civilize” and educate Indigenous peoples as early as 1789, based on a recommendation from then-Secretary of War Henry Knox.

Over the ensuing decades, in 120 of the 370 treaties made with Native people, the government promised to provide education and indicated that Christian missionaries could be paid to do it, according to research by Indian law experts Matthew Fletcher, citizen of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, and Wenona Singel, citizen of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, at Michigan State University’s Indigenous Law and Policy Center.

In 1819, Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act, creating a fund to pay Christian missionaries to establish schools in Indian Country in order to replace Native culture with Christian practices. In 1824, the fund supported 32 Christian boarding schools; by 1830, that number had risen to 52.

Funds from treaties, without consultation with tribes, were often used to help support the effort, according to the Native American Rights Fund.

“With respect to the history of missionary activities, it is probably enough to say that they date practically from the very beginning of the contact of the white man with the Indian. The policy of the government has always been to encourage missionary activities,” according to The Meriam Report, a 1928 study by what is now the Brookings Institution that surveyed conditions on Indian reservations in 26 states.

In 1869, Congress enacted President Ulysses S. Grant’s Peace Policy, which allowed the government to create its own boarding schools and authorized the coerced removal of Native children from their families to attend.

The policy institutionalized the concept of assimilation through boarding school education, but allowed church-run schools to continue to receive federal support.

Under the policy, Indian Country was effectively apportioned out to various Christian missionary groups, and Catholic leaders rushed to secure dominance on reservations with large trust funds, such as the Osage and Chippewa tribes, according to the archives at Marquette University.

The policy set off a conflict between Catholics and Protestants, leading to the creation in 1874 of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, a lobbying organization founded to protect and promote Catholic interests.

In 1908, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Quickbear v. Leupp that Native people could use their trust and treaty funds to pay for tuition in denominational schools, finding that the payments would not violate the separation of church and state because the funds belonged to tribes.

Catholics then set up a system in which Indigenous people could sign petitions, often with simple thumbprints, allowing the federal government to pay a portion of trust and treaty funds directly to the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, which in turn paid the individual schools.

Interestingly, the 1908 court describes the plaintiffs, who were Indigenous people of the Rosebud Sioux, as “citizens of the United States,” though Native people were not granted U.S. citizenship in South Dakota until the passage of the 1924 federal Indian Citizenship Act.

The court ruling made much of the Lakota people’s freedom of choice in its decision, but failed to note that Indigenous people at the time were prohibited from freely practicing their religion, selling their lands or spending their trust and treaty funds on food or supplies.

Year-by-year accountings of treaty fund payments were not among the archived documents, but a previous review of available records by ICT found that Indigenous people signed over more than $30 million in trust and treaty funds – adjusted to today’s dollars – to Catholic schools in just nine years scattered between 1910 and 1954.

Holy Rosary Mission School received Indian trust and treaty funds for at least 37 years, according to the ICT/Reveal review of available records.

ICT also found evidence of Catholic mission schools receiving additional federal monies, such as an additional $125 per child in trust and treaty funds for care and maintenance of neglected Indian children. Holy Rosary received those funds for 30 of its needy students in 1935, the equivalent of about $80,000 in today’s dollars, according to records at Marquette University.

Many schools also received children’s portions of federal rations for several years, according to the Marquette archives.

Additionally, Catholics were successful at private fundraising for the schools.

In 1884, the church created an annual Lenten collection to benefit the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions and African-American mission. Each diocese was required to send its funds from the collection to the bureau. The Lenten collection still generates funds for the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions.

Bureau Director William Ketchum also created The Indian Sentinel, an official fundraising magazine for the Society for the Preservation of Faith Among Indian Children. The magazine published three times a year until 1962 and featured first-hand accounts of missionaries.

From 1901 to 1914, the society raised $328,403 – or about $9 million in today’s dollars. In 1939, The Indian Sentinel generated $77,854, or about $1.5 million in today’s dollars.

In a notable example of Catholic fundraising success, the sisters at Holy Rosary reported in 1920 that they collected $40 from the citizens of the Pine Ridge reservation for starving children in Austria during the post-World War I years.

Nelson and others, however, complain that Red Cloud’s successful fundraising campaigns today imply that donations benefit a broad population on Pine Ridge, without mentioning the restrictions to get into the school.

“Red Cloud only takes the cream of the crop,” Nelson said. “Those with behavior or developmental problems or without family support can’t make it there.”

The Catholic Church also accumulated tribal lands from the U.S. government.

Under the Dawes Act of 1887, tribal lands held in common could be broken up into small parcels or allotments for individual heads of families and could be available free of charge to Christian missionaries.

Tribes lost more than 90 million acres of land because of the Dawes Act, according to the Indian Land Tenure Foundation. Unlike the lands allotted to individuals — which were held in trust by the government — churches were given tribal lands in a transfer known as “fee simple,” meaning the land could be used or transferred freely.

In his 1901 annual address, President Theodore Roosevelt described the act as a “mighty pulverizing machine to break up the tribal land mass.”

ICT/Reveal found documentation at the Marquette archives that the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions received more than 10,000 acres of allotted Indian lands to be used for schools from 1887 to 1934. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, documents show that the bureau divested itself of some of those lands by giving them to various Catholic dioceses and other entities.

The review of records recently by ICT/Reveal found that more than 7,000 acres of allotted Indian lands are still held by Catholic-affiliated organizations, including 1,118 acres held by the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions and 6,062 acres held by other Catholic entities.

The bureau transferred more than 700 acres of allotted lands to the nonprofit organization that ran the school, including the lands at Wounded Knee where hundreds of Lakota people were slaughtered in 1890 and left in a mass grave, according to bureau records at Marquette.

Red Cloud recently returned to the tribe about 40 acres, including the mass grave site. Records are unclear on the exact number of acres now held by Red Cloud.

ICT found that Holy Rosary purchased a number of other small tracts of land on Pine Ridge after allotment under the Dawes Act ended in 1934. According to a 1935 letter from the Department of the Interior to Rev. William Hughes, director of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, Congress issued an order allowing for sale of small tracts of restricted Indian lands to churches.

”I do believe that if tribal authorities wanted to sit down and have a conversation and demarcate all those properties, we’d be open to discussion,” Nadolny said, when asked if Red Cloud would consider giving more land back to the tribe.

“There are some unused parcels of property that I’d be happy to talk about with the tribal council,” he said.

Lack of transparency

Some details about boarding school history remain sketchy, however, because access to information has been limited by Catholic authorities.

Marquette University, a private Jesuit university in Milwaukee, is holding back decades of records showing student names, tribal affiliation, blood quantum and years of attendance at schools until information regarding blood quantum can be redacted.

Marquette archivists say portions of records are being scrutinized so they can black out some details to protect the privacy of long-dead students, but critics say it is a way to shield the church from uncomfortable realities.

Legislation is now pending in Congress that would help researchers get access to records at Marquette and other institutions. The bill would create a U.S. Truth and Healing Commission much like the one in Canada, with the ability to issue subpoenas for records for local churches and other government records related to attendance, illness, death, land and other correspondence.

The withholding of information has stymied a growing effort among tribes to locate the children who went missing or died while attending boarding schools, and access to Catholic Church archives remain a sticking point in uncovering the truths of what happened in the schools.

In the United States, the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis and the Jesuits have offered apologies or announced efforts to examine their history surrounding boarding schools, such as improving public access to their archives.

And although Catholics in Canada agreed to allow access to records under an agreement with that nation’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, many churches and orders continue to resist, citing privacy concerns.

Boarding school survivors and their ancestors here in the U.S. are finding similar resistance by churches.

Sacramental records, for example, which contain information about deaths and burials, are considered private by the church, protecting the past 100 years of data from public view. In some cases, however, sacramental records may be the only source of information about who lived and died at the schools.

An ordinance passed by the Oglala Sioux tribal council in the 1990s is being blamed for broad restrictions on Catholic boarding school reports made to the Bureau of Catholic Missions and to the U.S. government. In order to receive payment of trust and treaty funds to pay for tuition, each school was required to submit quarterly reports including names, tribal affiliation and blood quantum of students.

For reasons that remain unclear, the Oglala Sioux tribal council apparently passed an ordinance forbidding access in the 1990s to blood quantum information, according to Mark Thiel, former archivist at Marquette University and founder of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Mission archives.

Since that information is largely included in the same column as tribal affiliation in the archived records, however, the result is a restriction on access to important details that would help identify the students who died, ICT/Reveal found.

Tribal leaders told ICT/Reveal, however, that they were unaware of the ordinance or why it might have been passed. Tribal Council President Kevin Killer said he and the council will look into the history.

Marquette, meanwhile, has expanded the constraint beyond records for Oglala Sioux students, and now places the same restrictions on all of its records until archivists can redact the collection spanning more than 50 years.

Many of the government reports that should be in the National Archives, moreover, appear to have been lost.

In an earlier interview with ICT, Thiel said that fear of the unknown may be contributing to church leaders’ wariness about allowing open access to the archives. They don’t yet know what is contained in the records, he said.

“There are over 100 years of records in the collection,” Thiel said. “All of these secrets are locked into these filing cabinets and folders. It’s an amazing treasure trove.”

Amy Cooper Cary, head of special collections and university archives at Marquette, said the school takes its direction from the organization that donated the archival materials.

“None of our archives are closed to protect the Catholic Church,” Cary said. “They are closed in order to protect personal privacy.”

Nadolny said Red Cloud has recently hired a full-time researcher to help assemble the school’s history. He also pledged to investigate why certain records, such as sacramental records or school attendance logs, are being withheld.

Graduates at the Red Cloud Indian School in May 2022 received handmade quilts along with their diplomas. (Photo by Mary Annette Pember/ICT)

Looking ahead

The troubles of the past were mostly out of mind at the Red Cloud graduation ceremony in May.

Like most graduations, it was a mixture of jubilation and relief. But at Red Cloud, there was a tangible air of conquest among the students as they made their way across the stage and mingled with family afterwards.

Ruby Clifford, a diminutive elder from the Ute Indian Tribe, used a cane to make her way through the crowd to her grandson, Stryker Clifford. Stretching her arm to its full extent, she turned the tassel on his cap indicating he had graduated.

A tall, husky young man, Striker lowered his head for his grandmother.

It was a flash of tender vulnerability. His grandmother’s simple gesture offered a glimpse into a family moment that felt almost too intimate to bear. Months of grief, dogged struggle and love were concentrated into a few seconds, a flicker of exquisite pain that crowded the throat.

Someone handed Stryker a large photograph of a man who bore a strong resemblance to the young graduate. Stryker held the image close, high on his chest, as he and his grandmother posed for the cameras. It was a photo of his father, Robert Clifford, Ute, who had died from COVID-19 a few months earlier.

“He would have been so proud of you, grandson,” Ruby Clifford said.

Stryker smiled at the camera; yes, his dad would have been proud.

Families turned out for graduation day at Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, in May 2022, including Ruby Clifford, Ute, who posed for a photo with her grandson Stryker Clifford, Oglala Lakota/Ute. Stryker is holding a photo of his late father, Robert Clifford, who died in August 2021 just as Stryker was starting his senior year at Red Cloud Indian School. (Photo by Mary Annette Pember/ICT)

It was a moment of truth for all the graduates and their families – that they could have the benefits of a Western-style college preparatory education with its inherent access to an elite world and keep their Indigenous culture, language and traditions.

That is the unspoken gift that comes with a private Jesuit education — the social acumen and connections to help students navigate life outside of the reservation, the kind of knowledge that spells power in the White world.

But it still doesn’t address the harms of the past. Although Pope Francis apologized to Indigenous people in Canada in July for the cultural genocide of the residential school system there, no public apology or acknowledgement has been forthcoming in the U.S.

No one knows how many Indigenous children attended boarding schools here, or how many died without ever making it home to their families. No one knows how many are still missing.

But doors, including those at Red Cloud, are slowly being opened.

U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, the first Indigenous person to sit in a presidential cabinet, ordered an investigation of the U.S. boarding school system, and the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative released its initial report earlier this year identifying hundreds of boarding schools that operated across the U.S.

Chieko Noguchi, director of public affairs for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, said discussions are ongoing in the United States between church officials and Indigenous leaders after the Pope’s visit to Canada.

“The Holy Father’s penitential pilgrimage to Canada offers a unique opportunity to engage in real and honest dialogue on the issue of boarding school accountability here in the United States,” Noguchi said, in an emailed response to questions from ICT, “and it is a vital part of the process to inclusively discern how to go forward together as the Catholic Church walks with the impacted communities on a path towards healing.”

Red Cloud is among the Catholic organizations now taking the lead to confront and address its own boarding school past. It won’t be easy — Indigenous people on Pine Ridge and elsewhere are demanding truth and reparations after decades of silence from church officials.

“I feel like they are trying to do the right thing, but it’s a very touchy process. People are going to get angry no matter what they do,” Jade Ecoffey, a senior at Red Cloud, told ICT/Reveal. “The most important thing is that they not try to hide anything.”

Davidica Little Spotted Horse, a former student at Red Cloud, said the church needs to give back some of what it has taken.

“The Jesuits should do something that has a lasting, broad impact for the tribe, like providing mental health services, housing or funding for education,” she said.

But can an institution whose mission was to eradicate Native language, culture and spirituality guide education today?

“Catholicism was all about wiping out Lakota culture and now they want to co-exist and teach us our language and spirituality,” Ecoffey said. “I understand how people are having an internal conflict about that. Our spirituality and our traditions are in our blood. We’ve always found ways to survive and keep our language and culture alive.”

Yet struggles remain.

Stryker Clifford’s mother, Farrah Oliver, a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Tribe, said her son came very close to not being able to walk across the graduation stage with his classmates.

Oliver and Stryker’s father, along with several other siblings, attended Red Cloud and counted themselves as part of the “Red Cloud family.” Although they were divorced, they shared parenting responsibilities; Stryker lived with his father in the village of Wounded Knee.

Stryker’s father died in August 2021, just as the teen was starting his senior year.

“He was Stryker’s whole world,” Oliver told ICT. “His senior year was supposed to be this grand thing, you know? The feather-tying ceremony, the prom, graduation pictures and driving his dad’s Camaro.”

Stryker missed seven days of school and got behind in schoolwork. Then came the notice from school officials.

“At first they were understanding, but in October 2021 Stryker brought home a paper the school called a ‘Success Plan,’” Oliver said. “It called for no more unexcused absences, maintaining a certain GPA and other things.”

Noticeably lacking, however, was any input from Stryker or school plans to offer support.

Oliver met with school officials and reminded them that his father had died only weeks earlier, only to be told, “He’s not the only one to lose a family member this year,” she said.

But the family banded together to support him. Oliver quit her job in Rapid City and moved in with her son. Ruby Clifford moved back to Wounded Knee from the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in Utah to be with her grandson.

And by graduation, Stryker was about one-half credit shy of completing his high-school requirements, so Red Cloud administrators allowed him to participate in the graduation ceremony with the understanding that he would complete the work.

Oliver said it was a “huge accommodation” from school officials, but she is clearly disillusioned by the experience.

“If Red Cloud doesn’t embrace your potential, you just become a number to them,” she said.

Stryker is now nearly finished with one final online course and is planning to attend the University of South Dakota, Oliver said.

“He’s a really smart kid,” Oliver said. “Our family supports him 100 percent.”

Kathryn Styer Martinez at Reveal contributed to this report.

Reveal is a co-production of The Center for Investigative Reporting and PRX. The Center for Investigative Reporting engages and empowers the public through investigative journalism and groundbreaking storytelling in order to spark action, improve lives, and protect democracy. It produces multimedia reporting, including the Reveal public radio show and podcast, and theRevealNews.org website.

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help ICT (formerly Indian Country Today) carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

Red Cloud SchoolCatholic ChurchHoly Rosary MissionTruth And HealingReparationsReconciliationIndian Boarding SchoolsBuried SecretsPine Ridge

By

Mary Annette Pember, a citizen of the Red Cliff Ojibwe tribe, is a national correspondent for ICT.