Lindsay Whitehurst

Associated Press

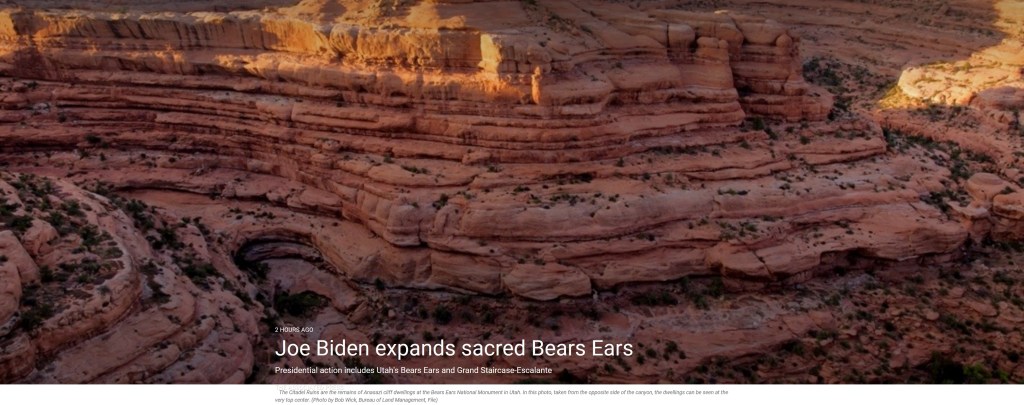

SALT LAKE CITY — President Joe Biden will expand two sprawling national monuments in Utah that have been at the center of a public lands tug-of-war that has played out over three presidential administrations, the state’s governor said Thursday.

Gov. Spencer Cox, a Republican, released a statement expressing disappointment in a decision by the administration to expand Bears Ears National Monuments and Grand Staircase-Escalante, which were downsized significantly under President Donald Trump.

They cover vast expanses of southern Utah where red rocks reveal petroglyphs and cliff dwellings and distinctive twin buttes bulge from a grassy valley. The Trump administration cut Bears Ears, on lands considered sacred to Native American tribes, by 85 percent and slashed Grand Staircase-Escalante by nearly half.

Cox’s statement did not include specifics how much of the monuments Biden plans to restore, and the White House and the U.S. Interior Department declined immediate comment.

Cox noted he had offered to work with the administration on a legislative solution.

“The president’s decision to enlarge the monuments again is a tragic missed opportunity — it fails to provide certainty as well as the funding for law enforcement, research, and other protections which the monuments need and which only Congressional action can offer,” he said in the statement released with other state leaders.

Hopi Chairman Timothy L. Nuvangyaoma said he is “happy” and “grateful for the advocacy of all those related to protecting Bears Ears and for the Hopi tribe” because it means a lot to the clan memberships.

“For Hopi, this is a significant step forward and the Biden administration did make some commitments to listen to Native America and Biden’s actions does prove that it is happening. We do need to protect these sacred sites that not only the Hopi tribe but other tribes find significant within their history.”

The chairman said he and the vice chairman will be headed to Washington, D.C.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Indigenous Cabinet secretary, traveled to Utah in April to tour the area before preparing a formal recommendation to President Biden.

Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, visited the monuments, becoming the latest federal official to step into what has been a years-long public lands controversy. https://platform.twitter.com/embed/Tweet.html?dnt=false&embedId=twitter-widget-0&features=eyJ0ZndfZXhwZXJpbWVudHNfY29va2llX2V4cGlyYXRpb24iOnsiYnVja2V0IjoxMjA5NjAwLCJ2ZXJzaW9uIjpudWxsfSwidGZ3X2hvcml6b25fdHdlZXRfZW1iZWRfOTU1NSI6eyJidWNrZXQiOiJodGUiLCJ2ZXJzaW9uIjpudWxsfSwidGZ3X3NwYWNlX2NhcmQiOnsiYnVja2V0Ijoib2ZmIiwidmVyc2lvbiI6bnVsbH19&frame=false&hideCard=false&hideThread=false&id=1380219354378342404&lang=en&origin=https%3A%2F%2Findiancountrytoday.com%2Fnews%2Fjoe-biden-to-expand-2-utah-national-monuments&sessionId=b31246f3cd0f7ee7df9267183db6a84aa51009f5&theme=light&widgetsVersion=fcb1942%3A1632982954711&width=550px

Utah Sen. Mitt Romney also criticized Biden by saying in a tweet Thursday that he “squandered the opportunity to build consensus” and find a permanent solution for the monuments.

“Yet again, Utah’s national monuments are being used as a political football between administrations,” Romney said. “The decision to re-expand the boundaries of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante is a devastating blow to our state, local and tribal leaders and our delegation … today’s “winner take all” mentality moved us further away from that goal.”

Jennifer Rokala, executive director of the Center for Western Priorities, applauded Biden’s decision and said she hopes it marks an initial step toward his goal of conserving at least 30 percent of U.S. lands and ocean by 2030.

“Thank you, President Biden,” Rokala said in a statement. “You have listened to Indigenous tribes and the American people and ensured these landscapes will be protected for generations to come.”https://platform.twitter.com/embed/Tweet.html?dnt=false&embedId=twitter-widget-1&features=eyJ0ZndfZXhwZXJpbWVudHNfY29va2llX2V4cGlyYXRpb24iOnsiYnVja2V0IjoxMjA5NjAwLCJ2ZXJzaW9uIjpudWxsfSwidGZ3X2hvcml6b25fdHdlZXRfZW1iZWRfOTU1NSI6eyJidWNrZXQiOiJodGUiLCJ2ZXJzaW9uIjpudWxsfSwidGZ3X3NwYWNlX2NhcmQiOnsiYnVja2V0Ijoib2ZmIiwidmVyc2lvbiI6bnVsbH19&frame=false&hideCard=false&hideThread=false&id=1446238172774637571&lang=en&origin=https%3A%2F%2Findiancountrytoday.com%2Fnews%2Fjoe-biden-to-expand-2-utah-national-monuments&sessionId=b31246f3cd0f7ee7df9267183db6a84aa51009f5&theme=light&widgetsVersion=fcb1942%3A1632982954711&width=550px

Trump’s cuts ironically increased the national attention to Bears Ears, Rokala said. She called on the federal government to increase funding to manage the landscape and handle growing crowds.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Indigenous Cabinet secretary, traveled to Utah in April to visit the monuments, becoming the latest federal official to step into what has been a yearslong public lands battle.

Former President Barack Obama proclaimed Bears Ears a national monument in 2016. The site was the first to receive the designation at the specific request of tribes.

The Bears Ears buttes, which overlook a grassy valley, are considered a place of worship for many tribes, according to Pat Gonzales-Rogers, executive director of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. The group incudes the Hopi Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni and Ute Indian Tribe.

The Trump administration’s reductions to Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante paved the way for potential coal mining and oil and gas drilling on lands that were previously off-limits. However, activity was limited because of market forces.

Conservative state leaders considered the size of both monuments U.S. government overreach and applauded the reductions.

Environmental, tribal, paleontological and outdoor recreation organizations sued to restore the monuments’ original boundaries, arguing presidents lack legal authority to change monuments their predecessors created. Meanwhile, Republicans argued Democratic presidents have misused the Antiquities Act signed by President Theodore Roosevelt to designate monuments beyond what’s necessary to protect archaeological and cultural resources.

The administration has said the decision to review the monuments was part of an expansive plan to tackle climate change and reverse the Trump administration’s “harmful” policies.

Indian Country Today contributed to this report.